Syrian Ostrich (?) / Little Owl (?), בת יענה, יענים, Struthio camelus syriacus (?) / Athene noctua (?)

Back to FaunaSyrian Ostrich (?) / Little Owl (?)

בת יענה (bat ya‘ana), יענים (ye‘enim [qere])

Struthio camelus syriacus (?) / Little Owl (?)

Hebrew Bible: כנף-רננים (Job 39:13, see below); בת יענה (bat ya‘ana) may possibly be an Little Owl (Athene noctua); Aramaic (and Rabbinic Literature): נעמית; Arabic: نَعام.

The etymology of the name בת יענה is uncertain. It may derive from the Arabic waʿnat, meaning “stony and unproductive soil” (BDB, 419; HALOT, 421) [1]. Some suggest that it stems from the Syriac yaʿnā / yaʿīn, meaning “greedy” (BDB, 419; HALOT, 421; Leibovitz & Bilik, 377). Others propose a Hebrew origin: ענייה or מענה (Leibovitz & Bilik, 377). The Life & Natural Sciences section discusses two main identifications: (1) Ostrich, as per the early translations; and (2) Eagle owl, as a possible bird of prey, based on the biblical context (see below).

Image gallery

Biblical data

Introduction

בת יענה (pl. בנות יענה) occurs eight times in the Hebrew Bible. The singular form is mentioned alongside birds of prey in the list of birds the Israelites are forbidden from eating (Lev 11:16; Deut 14:15). The plural form appears alongside other animals in descriptions of destruction, desolation, and mourning. In Isa 13:21–22, בנות יענה parallels אֹחים (owls) in a chiastic structure and appear in conjunction with ציים (beasts), שעירים (satyrs), איים (jackals), and תנים (dragons) (all NJPS). In Isa 34:11–15, בנות יענה occurs in the company of the תנים and what appear to be other avian species: קאת (jackdaw), קפוד (owl), ינשוף (great owl), ערב (raven), ציים (wildcats), איים (hyenas), שעיר (goat-demon), לילית (Lilith), קפוז (arrow snake), and דיות (buzzards) (all NJPS). In Jer 50:39, בנות יענה appears together with ציים (wildcats) and איים (hyenas) (all NJPS—though most of these identifications are highly doubtful). Otherwise, בנות יענה parallels תנים (Isa 34:13; Mic 1:8; Job 30:29) or appears adjacent to them (Isa 43:20).

The plural form יענים occurs once in the Hebrew Bible in Lamentations (4:3, qere). While there is no certainty that this form refers to the same animal that is called בת יענה, יענים here as well parallels תנים (qere; ketiv: תנין) and appears in the context of destruction and lament.

As the History of Identification discussion indicates, the ancient translations regularly identified the בת יענה as an “ostrich”. The bird that is referred to as רננים in Job 39:13–18 was also identified as an “ostrich” and therefore is discussed in this entry as well (see Exegetical Studies). However, this tradition is not compatible with the biblical data relating to בנות יענה, when assessing it in view of the ornithological information regarding the ostrich. Rather, the gathered information points to the assumption that בנות יענה should be identified as some sort of bird of prey (suggested below to be the Little owl). The Life & Sciences section discusses both options.

Distribution within the Bible

Two of the eight occurrences of בת יענה (pl. בנות יענה) are in legal texts. בת יענה is included in the two versions of the list of unclean birds (Lev 11:16; Deut 14:15), found in the laws regarding the animals the Israelites may or may not consume.

In five of the references, בנות יענה appears in the prophetic literature—in judgment prophecies against the nations (Babylon [Isa 13:21; Jer 50:39] and Edom [Isa 34:13]), in a prophecy concerning Israel’s salvation and the Return to Zion (Isa 43:20), and in a prophecy regarding the destruction of Samaria (Mic 1:8).

In addition, בנות יענה appears once in the wisdom literature (Job 30:29), and possibly also referred to as רננים in Job 39:13–18 (see Exegetical Studies).

The plural form יענים is only found in a lament regarding the fall of Judah and Jerusalem and the exile of the people (Lam 4:3, qere). [2]

Parts, Elements, Features that Are Specified in the Bible

An Unclean Bird Whose Consumption is Forbidden. בת יענה is mentioned amongst the birds the Israelites are forbidden to eat (Lev 11:16; Deut 14:15). Several bird names in these lists have been identified as carnivorous birds—and specifically as nocturnal birds of prey (Strigiformes)—a fact that helps explain their classification as unclean.

Residing in the Desert. Both בנות יענה in Isa 43:20 and יענים in Lam 4:3 are depicted as inhabiting in the desert: תכבדני חית השדה תנים ובנות יענה כי נתתי במדבר מים נהרות בישימן להשקות עמי בחירי, “The wild beasts shall honor Me, jackals and ostriches [so in LXX, Tg., Vulg., NJPS, NRSV; though this translation is questionable] for I provide water in the wilderness, rivers in the desert, to give drink to My chosen people”; בת עמי לאכזר כי ענים (כיענים) במדבר, “But my poor people has turned cruel, like ostriches [so in LXX, Tg., Vulg., NJPS, KJV, NRSV; though this translation is questionable] of the desert.”

Occupying Desolate Ruins. בנות יענה are portrayed as dwelling (together with other animals) in various desolate places—the ruins of the fallen Babylonian (Isa 13:19–22; Jer 50:39–40) and Edomite (Isa 34:10–15) kingdoms.

Howling. Mic 1:8 implies that the בת יענה wails or howls in mourning: אעשה מספד כתנים ואבל כבנות יענה, “I will lament as sadly as the jackals, as mournfully as the ostriches [so in Tg., Vulg., NJPS, NRSV; though this translation is questionable].”

Function in Context

The only realistic occurrences of בת יענה are in Lev 11:16 and Deut 14:15, where it is regarded as a bird the Israelites are forbidden to consume.

All the other incidences of בנות יענה have a symbolic function. The dwelling of בנות יענה in desolate ruins serves as a metaphor for fallen kingdoms (Isa 13:21; 34:13; Jer 50:39). In Isa 43:20 בנות יענה take part in a metaphor for God’s marvelous powers, the desert animals (בנות יענה and תנים) paying him homage for sustaining them in the wilderness. The wailing of בנות יענה is a simile for grief and mourning (Mic 1:8). The human affinity with בנות יענה functions as a metaphor for solitude and alienation from society (Job 30:29). יענים in Lam 4:3 have a symbolic function—there they serve as a simile for the fall of Judah.

Pairs and Constructions

בנות יענה (and יענים) are paralleled to תנים in four synonymous parallelisms (Isa 34:13; Mic 1:8; Job 30:29; Lam 4:3). And once more are בנות יענה juxtaposed with תנים (Isa 43:20).

End Notes

[1] BDB and HALOT point to a possible affinity between the name בת יענה in this sense (“daughter of the desert”) and the Arabic name abu eṣ-ṣaḥārāI, meaning “father of the plains / desert”.

[2] MT ketiv—כי ענים—is probably corrupt, an erroneous letter division leading to the splitting of one word into two. In numerous manuscripts, the ketiv form is identical to MT qere—כיענים (BHS, 1364).

Bibliography

Leibowitz, Yosef, and Elkana Bilik. 1954. “בת יענה.” Cols. 376–378 in vol. 2 of Encyclopaedia Biblica. Edited by Naphtali Herz Tur-Sinai, et al. 9 vols. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1950–1988 (Hebrew).

Contributor: Anat Alcalay, MA student in Biblical Studies

History of Identification

Identification History Table

| Hebrew | Greek | Aramaic | Syriac | Latin | Arabic |

English |

|||||

|

Reference |

MT | LXX | Revisions | Targumim | Peshitta | Vulgate | Jewish | Christian | KJV | NRSV |

NJPS |

| Lev 11:16 | בת היענה | στρουθός = ostrich | O: בַּת נַעֲמִיתָא

Ps.-J: בַּת נַעֲמִיתָא Tg. Sam: ברת יעניתה |

נעמא | strutionem | אלנעאמה | owl | ostrich | ostrich | ||

| Deut 14:15 | בת היענה | Στρουθός = ostrich | O: בַּת נַעֲמִיתָא

Ps-J: בְּרַת נַעֲמֵיתָא Tg. Sam: בת עניתה |

נעמא | strutionem | אלנעאמה | owl | ostrich | ostrich | ||

| Isa 13:21 | בנות יענה | σειρῆνες = sirens | J: בְּנַת נַעֲמִין | בנת נעמא | strutiones | בנאת אלנעאם | owls | ostriches | ostriches | ||

| Isa 34:13 | לבנות יענה | στρουθῶν (nom. στρουθόι) = ostriches | J: בַת נַעֲמָא | בנת נעמא | strutionum (nom.: strutionem) | בנאת אלנעאם | owls | ostriches | ostriches | ||

| Isa 43:20 | ובנות יענה | θυγατέρες στρουθῶν = daughters of ostriches | J: וּבְנָת נַעֲמִין | בנת נעמא | strutiones | בנאת אלנעאם | owls | ostriches | ostriches | ||

| Jer 50:39 (LXX 27:39) | בנות יענה | θυγατέρες σειρήνων = daughters of sirens | J: בְּנַת נַעֲמִין | בנת נעמא | strutiones | רעאל אלנעאם | owls | ostriches | ostriches | ||

| Mic 1:8 | כבנות יענה | θυγατέρων σειρήνων

(nom.: θυγατέρες σειρήνων) = daughters of sirens |

J: כִּבְנַת נַעֲמִין | ואבלא איך דברת ירורא

[= כבת תנים] [כופל את התרגום: מספד כתנים ועבדי מרקודתא איך דירורא] |

strutionum (nom.: strutionem) | רעאל אלנעאם | owls | ostriches | ostriches | ||

| Job 30:29 | לבנות יענה | στρουθῶν (nom.: στρουθόι) = ostriches | J: לִבְרַת נַעֲמֵיתָא

11QtgJob: [ ] ת יענה |

בנת נעמא | strutionum (nom.: strutionem) | רעאל אלנעאם | owls | ostriches | ostriches | ||

| Lam 4:3 | כיענים (Qere) | στρουθίον = ostrich (s.) | J: כְּנַעֲמַיָּא | ואיך נעמא במדברא] | strutio (s.) | פג׳אפיה כאלנעאם פי אלבריה | ostriches | ostriches | ostriches | ||

| Job 39:13 | כנף רננים | πτέρυξ τερπομένων = כנף מרננים (wing of the joyous) | J: גַדְפָא דְתַרְנְגוֹל | ܟܢܦܝ ܫܒܚܝܢ

= כנפי המשבחים |

pinna strutionum (wing of an ostrich) | goodly wings | ostrich wings | wing of the ostrich | |||

Discussion

The diverse translations of בת יענה, בנות יענה, and יענים (qere) raise significant issues in the history of identification. In most cases, the primary ancient translations—Septuagint, Aramaic Targumim, Peshitta, and Vulgate—consistently identify בנות יענה and יענים as “ostriches” (Greek: στρουθόι; Aramaic: בנת נעמין; Syriac: בנת נעמא; Latin: strutiones; Arabic: בנאת / רעאל אלנעאם).

Despite their minor status, the translations that deviate from the common ancient identification are of greater significance for the present discussion. First, the Samaritan Aramaic translation of Lev 11:16 and Deut 14:15 employs the equivalent ברת יעניתה / עניתה and in the Qumran Aramaic scroll of Job (11QtgJob) to 30:29 the word יענה clearly appears. As Talshir observes, the proposal that the Samaritan Pentateuch appears to have dressed the Hebrew יענה in Aramaic guise (יעניתה), is refuted by the fact that the ancient Aramaic translation of Job also uses the form יענה rather than the common Aramaic translation נעמיתא / נעמא. Talshir thus contends that יענה or יעניתה (with the common suffix for animal names in Samaritan Aramaic) was common Aramaic usage for ostrich. In his view, the choice of יעניתה is to be explained in light of the list of forbidden birds in the Samaritan version of Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14. יעניתה serving as the equivalent of רָחָם (Lev 11:18) or רָחָמָה (Deut 14:17) herein, the translator was prompted to opt for a different word for בת יענה (Talshir 2011, 67–68). Weiss argues that in the ancient Aramaic translation of Job יענה represents an untranslated Hebrew word—although, like Talshir, he entertains the possibility that יענה existed in an Aramaic dialect (Weiss 1977, 105).

Secondly, the Greek equivalents of בנות יענה in the Septuagint must also be considered in this context, as they seem to represent two different translational (and exegetical) traditions: (1) Six occurrences of בנות יענה are translated as στρουθόι (ostriches, Lev 11:16; Deut 14:15; Isa 34:13, 43:20; Job 30:29; Lam 4:3); (2) The other three occurrences (Isa 13:21; Jer 27:39 [MT 50:39]; Mic 1:8) employ (θυγατέρες) σειρήνων ([daughters] of sirens).[1] These readings of בנות יענה may reflect on the following exegetical tradition.

The Sirens were mythical creatures that originated in the Greek cultural world. According to Homer’s Odyssey, living on an island surrounded by rocks and cliffs, they were known for their alluring but fatal chanting:

First you will raise the island of the Sirens,

those creatures who spellbind any man alive,

whoever comes their way. Whoever draws too close,

off guard, and catches the Sirens’ voices in the air –

no sailing home for him, no wife rising to meet him,

no happy children beaming up their father’s face (Homer, od. 12.44–49).[2]

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the Sirens are the companions of young Persephone, Demeter’s daughter. When she is abducted by Hades, the god of the underworld, the Sirens, represented as bearing the head of a woman, are given wings in order to search for her:

Consider the not altogether different fate of the daughters

of Achelous, who had been Prosperpina’s companions

there at Pergus’ banks. These girls were turned into birds –

or their bodies at least were those of birds. Their shoulders and heads

were human still, and their voices, amazing, wonderful voices,

with the gift of astonishing song, were more than human, for these

are the Sirens. How did their transformation come about?

These were the same young ladies who fretted, mourned, and searched

high and low for their missing friend. They roamed the earth

[…] They prayed, therefore for wings

On which they could soar and glide, the better to search for their friend.

These prayers the celestial powers heard and granted forthwith (Ovid, Metam. 5.548–560).[3]

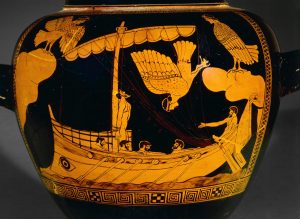

The visual evidence regarding the Sirens’ appearance is consistent with the written tradition reflected in the Odyssey and Metamorphoses. An Attic vase (480–470 BCE) depicting the scene from Homer’s Odyssey in which Odysseus’ ship passes by the Sirens, presents them—on a par with Ovid’s Metamorphoses—as birds with a woman’s head.[4]

The Greek sources evince that the Sirens were a type of bird—a human-avian hybrid—known for their delightful voices and singing. Do these features lie behind the Greek translators’ rendering of the biblical בת יענה as a Siren, בת signifying “woman” and יענה deriving from the root ענה (to sing, BDB, 777)? The fact that בת יענה appears in the Pentateuchal lists of forbidden birds may have served them as further “biological” support for this premise.

Papoutsakis offers a different explanation for the translator’s choice of the word “sirens” for בנות יענה, that rests on the assumption of a causal relationship between the Aramaic translation נעמא and Greek rendering (θυγατέρες) σειρήνων. Firstly, he draws attention to Lamech’s daughter Na’amah in the story of first inventors: ואחות תובל-קין נעמה (And the sister of Tubal-cain was Na’amah; Gen 4:22). While neither the MT nor any other ancient version provides any details about this figure, the Aramaic Targumim preserve a post-biblical tradition according to which Na’amah was the inventor and mistress of melody and song: ואחתיה דתובל קין נעמא היא הות מרת קינין וזמרין (Tg. Ps.-J to Gen 4:22); ואחתה דתובל קין הות נעמה בדיה קיניין וזמרין (Tg. Neof. ad loc).[5] Papoutsakis proposes that this exegesis arose from the homophonetic and homographic affinities between the name נעמה and the word נעימה (melody) and in relation to Gen 4:19–22, where Na’amah’s brothers and half-brothers are portrayed as inventors of the crafts and music (Papoutsakis 2004, 25–27):

19 וַיִּקַּח-לוֹ לֶמֶךְ שְׁתֵּי נָשִׁים שֵׁם הָאַחַת עָדָה וְשֵׁם הַשֵּׁנִית צִלָּה. 20 וַתֵּלֶד עָדָה אֶת-יָבָל הוּא הָיָה אֲבִי יֹשֵׁב אֹהֶל וּמִקְנֶה. 21 וְשֵׁם אָחִיו יוּבָל הוּא הָיָה אֲבִי כָּל-תֹּפֵשׂ כִּנּוֹר וְעוּגָב. 22 וְצִלָּה גַם-הִוא יָלְדָה אֶת-תּוּבַל קַיִן לֹטֵשׁ כָּל-חֹרֵשׁ נְחֹשֶׁת וּבַרְזֶל וַאֲחוֹת תּוּבַל-קַיִן נַעֲמָה.

19 Lamech took to himself two wives: the name of the one was Adah, and the name of the other was Zillah. 20 Adah bore Jabal; he was the ancestor of those who dwell in tents and amidst herds. 21 And the name of his brother was Jubal; he was the ancestor of all who play the lyre and the pipe. 22 As for Zillah, she bore Tubal-cain, who forged all implements of copper and iron. And the sister of Tubal-cain was Na’amah.

Hereby, the Aramaic Targumim resolve the difficulty that arises from the fact that Na’amah is the only person in this list that is not presented as an inventor by assigning her an invention that corresponds with the biblical context.

Papoutsakis then suggests that the Greek translation σειρῆνες derives from an Aramaic paronomasia between נעמא (“ostrich”) and the name of the primordial women נעמה (in Ps.-J.: נעמא), whom the Targumim portray as the mistress of song, as a type of siren. This Targumic exegesis, he contends, represents a late record of an early tradition that had developed before the septuagintal translation. He believes that in the Aramaic-speaking communities—the Septuagint translators amongst them—an associative link between Na’amah the songstress (מרת קינין וזמרין) / siren and the ostrich was formed. This in turn led to the translator’s choice of the word σειρῆνες as an equivalent of בנות יענה (ibid, 31).

The secondary English translations reflect the uncertainty and disagreement over the identity of בת יענה, following two principal directions. The first espouses the ancient translational tradition, identifying בת יענה as an ostrich (NRSV, NJPS). The second regards it as a nocturnal bird of prey, or more specifically, as some species of owl from the Strigidae family (KJV). The identification of בת יענה as an ostrich does not coincide with the biblical data relating to בנות יענה, when assessing it in view of the ornithological information regarding the ostrich. Rather, the gathered information points to the assumption that בת יענה should be identified as some sort of bird of prey, as KJV suggests. See more in the Life & Sciences section.

Note that כנף רננים (Job 39:13) is also translated as “wing of an ostrich” by the Vulgate, NRSV, and NJPS. These translations correspond to the principal identification proposals that will be discussed in the Life & Natural Sciences section.

End Notes

[1] The word σειρῆνες also serves as an equivalent of תנים in Isa 34:13, 43:20, and Job 30:29, wherein בנות יענה are juxtaposed with or parallel תנים.

[2] The English translation follows Fagles 1995.

[3] The English translation follows Slavitt 1994.

[4] The vase, held in the British Museum, is cataloged as the “Siren Vase”: see http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=399666&partId=1.

[5] Papoutsakis (2004, 27–29) understands קינין here as “song,”, in a neutral sense, rather in the negative sense the word קינה gained in biblical Hebrew.

Bibliography

Fagles, Robert, trans. 1996. Homer. The Odyssey. New York: Penguin.

Papoutsakis, Manolis. 2004. “Ostriches into Sirens: Towards an Understanding of a Septuagint Crux.” Journal of Jewish Studies 55(1): 25–36.

Slavitt, David R., trans. 1994. Ovid. The Metamorphoses. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Talshir, David. 2012. Living Names: Fauna, Places and Humans. Asuppot VI. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute (Hebrew).

Weiss, R. 1977. “The Aramaic Targum of Job from Qumran Cave 11.” Pages 101–110 in vol. 1 of Proceedings of the Sixth World Congress of Jewish Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 13–19 August 1973. Edited by Avigdor Shinan. Jerusalem: The World Union of Jewish Studies. (Hebrew).

Contributor: Anat Alcalay, MA student in Biblical Studies

Life & Natural Sciences

ID

Belonging to the Struthionidae family (Cramp & Simmons 1977), the ostrich is currently regarded as comprised of four extant subspecies characterized by distinctive phenotypic markers. A fifth—S.c. syriacus, whose range once reportedly extended into Arabia—is now considered extinct (Brown, et al. 1982).

The largest non-flying bird today, the ostrich ranges between 2 and 2.8m in length and 63 and 145kg in weight. It has a long, thick, flexible, bare neck with a very gentle plume, a strong tendon twisting between the cervical vertebrates (Deeming 1999). The male’s reproductive system is reminiscent of mammals—a pair of testicles and a penis that grows on the ventral side of the cloaca opening during the breeding season in order to stimulate the female’s clitoris and ovulation from the sole ovary (Deeming 1999). Its extra-long trachea and large lungs, combined with air sacs penetrating its hollow bones, channel a continuous flow of oxygen to its massive muscles (Donegan 2002).

Historically, the ostrich was widely distributed across Africa and the Arabian Peninsula to the Syrian Desert. It has now become extinct in many locations, however—including Libya, Syria, and Palestine (according to Tristram [1884], the ostrich exists in eastern Moab/Jordan). Recently, it has also declined in the northern regions of its main area of distribution and the southern strip of Central Africa, now primarily populating a continuous strip between Ethiopia in the east and Mali and Mauritania in the west. Re-introduced in some parts of South Africa, populations can also be found in marginal areas such as the tropical region near the equator and high and cold areas on the African continent (Cooper, et al. 2008).

Life History

The ostrich lays 15–60 eggs in the ground. The chicks emerge simultaneously, open-eyed and independent self-feeders. Leaving the nest after 11 days, they reach full sexual maturity and independence at 4/5 years old (Shanawany & Dingle 1999). In nature, ostriches live as long as 11 years (Carboneras 1992).

Characteristics that Appear in the Bible

An unclean bird. בת יענה occurs in both lists of birds the Israelites are forbidden to eat (Lev 11:16; Deut 14:15). Identifying it as an ostrich, the Mishna Sages called it by its Aramaic name, Naa’mit and explained this categorization on the basis of its physical features (no back hind toe, no crop and pilled gizzard (Hulin 64b). In reality it has just one and a half toes, no crop, but three stomach chambers for different purposes (Cramp & Simmons 1977).

Residing in the desert and desolate places. Ostriches live in deserts or Savanna-like plains scattered with low or exposed soil with no infrastructures to impede their high-speed running. No evidence existing that their preferred habitat is ruins, therefore, the biblical בת יענה is more likely an owl, see separate entry on the כוס, Little owl, Athene noctua.

Running. A highly cursorial flightless animal, the ostrich is known as the fastest biped with the greatest capacity for long-endurance (Alexander, et al. 1979). In times of danger or excitement, the males may reach a speed of 70 km/h in short sprints. Their average speed for distances over half an hour is about 50 km/h (Davies 2003; Donegan 2002). They also run in circles, seemingly on tiptoe, with their wings raised and spread (Tuckwell & Rice 1993; Sauer 1969).

Breeding. Ostriches mate polygynandrously, both sexes coupling with multiple partners (Kimwele & Graves 2003). A dimorphic species, the males are ostentatious, the females quiet and camouflaged, adapting themselves to the desert and sandy landscape color (Bertram 1992; Lambrechts, et al 2004). Breeding primarily from the end of the winter season through to summer, the male and female mate with various partners in the group. Both use a varied repertoire of visual displays, many making use of their wings (Bubier, et al. 1996).

As the males begin their courtship, their legs, necks, and faces turn red and shiny (Davies and Bertram 2003). The ritual rivalry between males becomes more and more frequent until they appear to be chasing in groups, their wings held high and performing a kind of a dance ritual. Chasing after females in a similar fashion at the same time, here they flap their tails. The male establishes his position by his stature and high tail position, accompanied by a whistling or snoring. In his passion, his genitals turn a brilliant reddish hue and protrude, imbued with a strong smell of urine (Bubier, et al. 1996). During courtship, the male clings to the female, both performing a vigorous synchronized eating ritual. As their passion rises, they circumambulate around the chosen or symbolic nesting territory. The male then raises his wings alternately, from right to left, waving the feathers of its white wings. Abruptly, he falls to the ground and begins to nest symbolically, in what appears to be an exaggerated manner, spreading dust as his wings sweep the ground. He then twists his neck, the female responding with bowed head, wings, and tail. When fully kneeling, she invites the male to copulate. He rises on his back, flapping his wings, and bending his head down and knocking it rapidly. The female then throws herself to the ground, with her tail raised and neck spread out. Finally, the male rises to his feet and grinds gently into the ground (Bubier, et al. 1996). No scientific evidence thus exists to support the traditional belief that the ostrich buries its head in sand (Pocock 1955). The male digs several holes with its feet—less shallow and in the center of the nesting territory this time.

Nesting upon the ground. The main female (“female alpha”) is the first to lay eggs, choosing the nest—a hole scraped in the ground—she favors (Bertram 1992; Deeming 1999). The eggs are left unattended for about two weeks before incubation begins. During this period, they are highly vulnerable to predators due to their bright white color. At the same time, however, they return radiation and are protected from excessive radiation and heat. Although up to 18 females lay in the same nest, only the male and female alpha incubate (for 42–44 days) and provide parental care (Sauer & Sauer 1966). A spectrographic study comparing the interior of the central and other eggs evinced no color difference between them, suggesting that the ostriches cannot identify their own eggs (Sauer & Sauer 1966). A pair of ostriches can only successfully incubate about 20 eggs of an average of 40 in and around the nest, the eggs shifting slightly as the incubation begins to change their position—most likely to stimulate fetal growth. Incubation lasts about a month, the eggs being protected by both male and female. The camouflaged female incubates during the day, the male replacing her at night if necessary (Jarvis, et al. 1985).

In protection of their eggs, females may on occasion perform the “injured bird” game in order to drive the intruder out of the nest (Brown, et al. 1982; Bertram 1992).

Their eggs are the largest in the avian world, reaching 15 cm in size and two millimeters in thickness. They are thus very difficult to crack—the only bird capable of doing so being the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus), which throws stones at the egg shells in order to break and eat them.

The chicks hatch with a thorny brownish fuzz after about four months. Well protected by their parents, they leave the nest to eat. By the time they are one year old, they have become independent, spending their time in a close-knit peer group (Bertram 1992).

Cruelty. The ostrich can be very dangerous to human beings or other intruders who invade its territory, wittingly or unwittingly, during the breeding season (Davies 2003). Its strong feet, long central finger (10cm), and strong claws make it capable of killing a predator or person with a well-directed kick.

Mourning howls. When under threat or in danger, the ostrich produces callings that sound like mourning howls, rising from the bottom of its throat. Other sounds, such as whistles and snoring, form part of the courtship display. During the rest of the year, however, ostriches usually remain very quiet (Bubier, et al. 1996).

Stupidity. With its relatively small head, the ostrich is frequently considered less intelligent than other birds (e.g., Pliny, Nat. [Bostock & Riley]). Its navigability and survival fitness skills are remarkable, however (Deeming 1999). Its misfortune is a function of the fact that it has always been sought after by human beings. Its eyes are among the largest and most developed in the animal kingdom. Heavier than its brain, they can identify relatively small objects from a great distance, being equipped with long black lashes that block desert dust and radiation (Deeming 1999).

Other Characteristics

Movement. The ostrich is a sedentary species that tends not to move long distances. As a true bipedal, it stands on its feet for most daylight hours, eating, walking and standing whenever not dust-bathing, copulating, nesting, or fighting over territory (Sauer & Sauer 1966; Alexander, et al. 1979). Unless disturbed or on moonlight nights, it is not active in the dark (Degen, et al. 1989).

Social patterns. A social species, the ostrich thrives in small groups of five to 50, led by an alpha female, also relying on the vigilance of fellow big-game mammals—zebras and antelopes (Donegan 2002). Outside the breeding season, ostriches tend to form small mixed-age and -gender groups, especially around water holes—although they do not usually need to drink and are able to get liquids mainly from their food (Berry & Louw 1982; Williams, et al. 1993; Cooper, et al. 2008). Fond of water, they take every opportunity to bathe (Brown et al 1982).

Females often form social bonds, gathering together (Sauer 1969). The males kick-fight to determine the hierarchical pecking order and eliminate competitors, tending to run in circles within their own territory.

In recent decades, the IUCN has defined the ostrich as a species without concern— despite its fragmented populations and declining number of individuals (BirdLife International 2018). The species is common in captivity, many ostriches being raised in breeding farms in around 50 different countries across the globe (Deeming 1999).

Diet. The ostrich is omnivorous, feeding primarily on insects (especially grasshoppers and beetles), reptiles, and rodents. In vegetarian terms, it prefers rootlets, seeds, fruits, and leaves (Milton, et al. 1994; Jamroz 2000; Williams, et al. 1993). Unlike other birds, its powerful broad, flat beak enables it to crush and grind food, expertly removing stiff leaves and grasses (Milton, et al. 1994). Swallowing stones and debris for better digestion (Williams, et al. 1993; Cooper 2006), it ingests cellulose, 60 percent of its energy being gained from food.

Used and hunted by humans. Ostriches are rarely hunted by big predators (Bertram 1992; Davies 2003). While their eggs are broken and destroyed by Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus) (Thouless, et al. 1989), human beings have collected them from time immemorial, storing liquids in them and using them in the art-jewelry industry, etc. (Bertram 1992) (see section 4, Material Culture). They were traditionally hunted extensively for their low-fat meat (their exposed necks being a particularly sought-after item) (Cooper, et al. 2008; Bertram 1992), high-quality leather (boots and clothing), and plume feathers (pillows and blankets) (Bertram 1992). Aharoni (1924) notes that the Persian and Egyptians made fans from their primaries feathers with which to decorate horses and camels. The intensive hunting, capture, and egg-collecting of the Syrian ostrich (primarily in the nineteenth century) on big farms led to their extinction at the beginning of the twentieth century (Jennings 1986; Deeming 1999). Facets of extinction include overgrazing of acacia trees in the savanna, as its main food (Thiollay 2006).

Bibliography

Aharoni, I. 1924. Animal Life. Tel Aviv: Kohelet (Hebrew).

Alexander, R. McN., et al. 1979. “Mechanics of Running of the Ostrich (Struthio camelus).” Journal of Zoology 187(2): 169–178.

Berry, H. H., and G. N. Louw. 1982. “Nutritional Balance between Grassland Productivity and Large Herbivore Demands in the Etosha National Park.” Madogua 13: 141–150.

Bertram, B. C. R. 1992. The Ostrich Communal Nesting System. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

BirdLife International. 2018. “Struthio camelus.” The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T45020636A132189458.en. Accessed on 4 August 2020. Brown, L. H., E. K. Urban, and K. Newman. 1982. Birds of Africa. London: Academic Press.

Carboneras, C. 1992. “Family Anatidae (ducks, geese, and swans).” Pages 536–628 in vol. 1 Ostrich to Ducks of Handbook of the Birds of the World. Edited by J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions.

Bubier, N. E., et al. 1996. “Courtship Behaviour of Ostriches in Captivity.” Pages 19–20 in Proceedings of the Ratite Conference: Improving our Understanding of Ratites in a Farming Environment. Edited by D. C. Deeming. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cooper, R. G. 2006. “Structure and Function of the Ostrich (Struthio camelus var. domesticus): Gut: Nutritional Impact.” Page 361 in Avian Gut Function in Health and Disease: Poultry Science Symposium Series 28. Edited by G. C. Perry. Wallingford, UK/Cambridge, MA: CABI.

Cooper, R. G., et al. 2008. “Ostrich (Struthio camelus) production in Egypt.” Tropical Animal Health and Production 40(5): 349–355.

Cramp, S., and K. E. L. Simmons. 1977. “Order struthioniformes.” Pages 37–41 in vol. 1 Ostrich to Ducks of Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa: The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Edited by S. Cramp, et al. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davies, S. J. J. F. 2003. “Birds I: Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins”. Pages 99–101 in vol. 8 of Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia. 2nd ed. Edited by M. Hutchins. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

Davies, S. J. J. F., and B. C. R. Bertram. 2003. “Ostrich.” Pages 34–37 in Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds. Edited by C. M. Perrins New York: Firefly Books.

Deeming, D. C. 1999. The Ostrich: Biology, Production and Health. Wallingford, UK: CABI.

Degen, A. A., et al. 1989. “Time-Activity Budget of Ostriches (Struthio camelus) Offered Concentrate Feed and Maintained in Outdoor Pens.” Applied Animal Behaviour Science 22(3): 347–358.

Donegan, K. 2002. “Struthio camelus”. Animal Diversity Web: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Struthio_camelus/. Accessed on 5 August 2020.

del Hoyo J, Elliott A and Sargatal J (eds). 1999. Handbook of the

birds of the world, vol. 5: barn owls to hummingbirds

Jamroz, D. 2000. “Feeding Ostriches and Emus: Physiological Basis and Nutritional Requirements—A Review.” Prace i Materialy Zootechniczne 56: 51–73.

Jarvis, M. J. F., et al. 1985. “Breeding Seasons and Laying Patterns of the Southern African Ostrich Struthio camelus.” Ibis 127: 442–449.

Jennings, M. C. 1986. “The Distribution of the Extinct Arabian Ostrich Struthio camelus syriacus.” Fauna of Saudi Arabia 8: 447–461.

Kimwele, C. N., ans J. A. Graves. 2003. “A Molecular Genetic Analysis of the Communal Nesting of the Ostrich (Struthio camelus).” Molecular Ecology 12(1): 229–236.

Milton, S. J., et al. 1994. “Food Selection by Ostrich in South Africa.” Journal of Wildlife Management 58(2): 234–248.

Lambrechts, H., et al. 2004. “The Influence of Stocking Rate and Male:Female Ratio on the Production of Breeding Ostriches (Struthio camelus spp.) under Commercial Farming Conditions.” South African Journal of Animal Science 34(2):87–96.

Bostock, J., and H. T. Riley, trans. 1855. Pliny. The Natural History. London: Taylor and Francis.

Pocock, A. 1955. “The Ostrich Hiding Its Head – A Myth.” African Wildlife 9:234–236.

Sauer, F. 1969. “Interspecific Behaviour of the South African Ostrich.” Ostrich 40(Suppl.): 91–103.

Sauer, E. G. F., and E. M. Sauer. 1966. “Social Behaviour of the South African Ostrich, Struthio camelus australis.” Ostrich 37(Suppl.): 183–191.

Shanawany, M. M., and J. Dingle. 1999. Ostrich Production Systems. FAO Animal Production and Health Paper 144. Rome: FAO.

Thiollay, J. -M. 2006. “Severe Decline of Large Birds in the Northern Sahel of West Africa: A Long-term Assessment.” Bird Conservation International 16(4): 353–365.

Thouless, C. R., J. H. Fanshawe, and B. C. R. Bertram. 1989. “Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus and Ostrich Struthio camelus Eggs: The Origins of Stone-throwing Behaviour.” Ibis 131: 9–15.

Tristram, H. B. 1884. The Survey of Western Palestine: The Fauna and Flora of Palestine. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

Tuckwell, C., and S. Rice. 1993. The Australian Ostrich Industry. Adelaide: Primary Industries.

Williams, J. B., et al. 1993. “Field Metabolism, Water Requirements and Foraging Behavior of Wild Ostriches in the Namib.” Ecology 74(2): 390–404.

Contributor: Dr. Haim Moyal, Ornithologist, Zoologist, and archaeologist, Levinsky-Wingate College