Quail, שלו, Coturnix coturnix

Back to FaunaQuail, common quail (from Old French “quaille,” etymology unknown)

שלו (slav)

Coturnix coturnix (from Latin quocturnix, imitative of the bird’s cry, onomatopoeia)

German: Wachtel (“rock hen, chukar”)

Spanish: Codorniz común

French: Caille des blés (see Moyal 2001)

Modern Hebrew: שליו נודד (etymology unknown)

Arabic: (1) سلوى (slawa); (2) sumna (“fat”—which the bird accumulates before migration seasons) (Moyal 2004)

Image gallery

Biblical data

Introduction

The term שלו occurs four times in the Hebrew Bible, twice in narratives within the Pentateuch (Exod 16:13; Num 11:31, 32) and once in Psalms (Ps 105:40). It is also alluded to in the expression עוף כנף (“winged bird”) in Ps 78:27. All the occurrences are of a realistic nature. Serving as a source of food, it appears in the accounts of God providing Israel with the manna (מן) on their journey from Egypt to Canaan through the wilderness. Together with the ornithological information, the features attributed to שלו in the Hebrew Bible affirm its identification as the quail.

The etymology of the name שלו is uncertain. It may derive from the Arabic salāy “to be fat” (HALOT, 1331). The Arabic (سلوى, salwā) and Syriac (salway) preserve a phonetically similar tradition (BDB, 969). See the Life & Natural Sciences section below.

Distribution within the Bible

Three of the five references to שלו appear in two narratives in the Pentateuch (Exod 16:13; Num 11:31, 32). In Exodus 16, the Israelites complain to Moses and Aaron that they are hungry, questioning the reason for having left Egypt where they had enjoyed meat and bread (v. 3). In response, God promises them: בין הערבים תאכלו בשר ובבקר תשבעו לחם “By evening you shall eat flesh, and in the morning you shall have your fill of bread” (v. 12). This is literally fulfilled, as by the evening the שלו comes upon the Israelite campsite, and by dawn comes the bread in the form of manna (vv. 13–15).

The narrative in Numbers 11 similarly relates to the Israelites’ murmurings in the wilderness. Here, they specifically grumble about the lack of meat: וישבו ויבכו גם בני ישראל ויאמרו מי יאכלנו בשר “and then the Israelites wept and said, ‘If only we had meat to eat!’” (v. 4). Vv. 6–9 suggest another description regarding the arrival of manna. God responds to their objection that all they have to eat is manna by sending them שלוים (vv. 31–32). This caviling leads to their punishment, God striking the מתאוים “desiring people” dead as they eat the meat. Buried where they lie, the place is named קברות התאוה “the graves of desire” (vv. 33‒34).

The two other references of שלו occur in the poetic literature—Ps 78:27 and 105:40. Both these texts are based on pentateuchal traditions (oral or written)—possibly even resting on the passages discussed above. Ps 78:21–31 retells the incident recorded in Num 11 in a concise fashion, employing similar language (cf. Ps 78:26 // Num 11:31; 78:28 // 11:31; 78:30–31 // 11:33). At other times, it is closer to the version in Exodus 16 (cf. Ps 78:24 // Exod 16:4a; 78:29 // 16:3a). Thus rather than the שלו in Exod 16:13 and Num 11:31, 31, v. 27 speaks of a עוף כנף (“winged bird”).

The pentateuchal narratives indicate that the name שלו addresses an edible animal of some sort, the שלו being parallel to בשר (“meat,” “the flesh of animals,” Exod 16:12‒13; Num 11:18, 33). Ps 78:27 elaborates, clarifying that it is a bird—although not signifying the specific species.

In Psalm 105, the episode forms part of a list of God’s deliverances of Israel, including the plagues (vv. 27–36) and Exodus (vv. 37–38).

Parts, Elements, Features that Are Specified in the Bible

An Edible Bird. In all its occurrences, the שלו appears as a source of food given to Israel by God (Exod 16:13; Num 11:31, 32; Ps 78:27; 105:40). Its flesh can thus be presumed to have been edible from both a biological-physiological and legal perspective. The fact that שלו is absent from the list of unclean birds that Israel is forbidden to eat (Lev 11:13–19; Deut 14:11–18) is consistent with the portrayal of שלו in the Pentateuch and Psalms.

Appearance in the Eastern Mediterranean. According to the pentateuchal narratives, God gave the Israelites quail on two occasions—once prior to their arrival at Mount Sinai (Exod 19:2) and once just after their departure thence (Num 10:12). While we do not know where the author thought “Mount Sinai” or “Sinai Desert” to be, the wilderness between Egypt and Canaan indicates the eastern part of the Mediterranean.

Arrival in Spring. The quail are said to have arrived in Iyar, the second month of the year—i.e., at the height of spring: ויסעו מאילם ויבאו כל עדת בני ישראל אל מדבר סין אשר בין אילם ובין סיני בחמשה עשר יום לחדש השני לצאתם מארץ מצרים “Setting out from Elim, the whole Israelite community came to the wilderness of Sin, which is between Elim and Sinai, on the fifteenth day of the second month after their departure from the land of Egypt” (Exod 16:1); ויהי בשנה השנית בחדש השני בעשרים בחדש נעלה הענן מעל משכן העדת. ויסעו בני ישראל למסעיהם ממדבר סיני “In the second year, on the twentieth day of the second month, the cloud lifted from the Tabernacle of the Pact and the Israelites set out on their journeys from the wilderness of Sinai” (Num 10:11–36, immediately followed by the demand for meat [Num 11]).

Arrival in the Evening. According to Exod 16:13, the miraculous שלו appeared in the evening: ויהי בערב ותעל השלו ותכס את המחנה “In the evening quail appeared and covered the camp.”

Arrival from the Sea. Num 11:31 describes the miraculous appearance of the שלוים as coming from the sea, a wind distributing them across the whole camp site: ורוח נסע מאת יהוה ויגז שלוים מן הים ויטש על המחנה “A wind from the Lord started up, swept quail from the sea and strewed them over the camp.”

Spreading Out. Following the description of the miracle (v. 31), Numbers 11 depicts the Israelites laying the שלוים out on the ground: ויאספו את השלו […] וישטחו להם שטוח סביבות המחנה “The people set to gathering quail […] and they spread them out all around the camp” (v. 32).

Consumption as a Cause of Death. The account of the Israelites’ demand for meat in Numbers 11 and the shorter version in Psalm 78 both end with their punishment by God; The “desiring” Israelites die while eating the bird’s meat: הבשר עודנו בין שניהם טרם יכרת ואף יהוה חרה בעם ויך יהוה בעם מכה רבה מאד “The meat was still between their teeth, nor yet chewed, when the anger of the Lord blazed forth against the people and the Lord struck the people with a very severe plague” (Num 11:33); לא זרו מתאותם עוד אכלם בפיהם ואף אלהים עלה בהם ויהרג במשמניהם ובחורי ישראל הכריע “They had not yet wearied of what they craved, the food was still in their mouths when God’s anger flared up at them. He slew their sturdiest, struck down the youth of Israel” (Ps 78:30–31).

Function in Context

All the occurrences of שלו are of a realistic nature. The שלו is always regarded as a source of nourishment for Israel, appearing only in the accounts of God providing the people with food during their journey in the desert.

Contributor: Anat Alcalay, MA student in Biblical Studies

History of Identification

Identification History Table

| Hebrew | Greek | Aramaic | Syriac | Latin | Arabic | English | |||||

| Reference | MT | LXX | Revisions | Targumim | Peshitta | Vulgate | Jewish | Christian | KJV | NRSV | NJPS |

| Exod 16:13 | שְּׂלָו | ὀρτυγομήτρα

= quail-mother LSJ: “a bird which migrates with quails, perhaps corncrake, landrail, Rallus crex” |

O: סְלָו

CAL: quail PJ: פיסייונין CAL: pheasant N: סלוי / שלויין Nm: סלויְ / פיסיוניוון S: סלויתה |

s.lw_y

CAL: quail |

coturnix

LS: quail |

quail | quail | quail | |||

| Num 11:31 | שַׂלְוִים | ὀρτυγομήτραν | O: סְלָיו

PJ: שלוי N: סלויין S: סלבי |

slwy | coturnices | quail | quail | quail | |||

| Num 11:32 | שְּׂלָו | ὀρτυγομήτραν | O: סְלָיו

PJ: סלוי N: סלווי S: סלויתה |

slwy | coturnicum | quail | quail | quail | |||

| Ps 105:40 | שְׂלָו | ὀρτυγομήτρα | פיסיונין | mˀkwltˀ

= food |

ortygometran

(transliterat-ion of Greek ὀρτυγομήτρα “quail-mother”) |

quail | quail | quail | |||

| Wis 16:2 | – | ὀρτυγομήτραν | – | slwy | ortygometram | quail | quail | – | |||

| Wis 19:12 | – | ὀρτυγομήτρα | – | slwy | ortygometra | quail | quail | – | |||

| 2 Esd 1:15 | – | – | – | – | coturnix | quail | quail | – | |||

Discussion

All occurrences of שְּׂלָו in the Hebrew Bible relate to a bird the Israelites ate in the wilderness. Despite lacking any direct Hebrew basis, the apocryphal passages that refer to a bird in the same episode (Wis 16:2, 19:12; 2 Esd 1:15) are also taken into consideration here.

The Septuagint consistently renders שְּׂלָו as “quail-mother” (ὀρτῠγομήτρα: ὄρτυξ “quail” + μήτηρ “mother”). According to LSJ, the term refers to “a bird which migrates with quails, perhaps corncrake, landrail, Rallus crex.” The lexeme ὄρτυξ does not occur anywhere in the Septuagint.

The Targumim mostly render שְּׂלָו by its Aramaic cognate סלו (quail). The Peshitta consistently uses the equivalent slwy (quail). Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Exod 16:13, Targum Neofiti marginalia on that verse, and Targum of Psalms all employ forms of פסינא (pheasant), however. The Vulgate alternates between coturnix (quail) and ortygometra—a transliteration of the Greek ὀρτῠγομήτρα (quail-mother) used by the Septuagint.

Contributor: Dr. Raanan Eichler, Department of Bible Studies, Bar Ilan University

Life & Natural Sciences

ID

The Quail belongs to the Phasianidae family, part of the Galiformes order (Cramp & Simmons 1980). 10 species of quails currently exist in the world, but just one species (coturnix coturnix) occurs in the wild in Israel (Del Hoyo et al. 1994, Shirihai 1996).

Sub–species in Israel and the Levant

Several sub–species of the common quail exist in Central, East, and South Africa, and Madagascar (Alderton 1992). Only one sub–species—Coturnix c. coturnix—is native to Israel and the Levant.

Recent studies evince that most re–released quails are genetically contaminated, being a hybrid between this species and the well–known domesticated species Coturnix japonica (Puigcerver et al. 1999; Barilani et al. 2005; Amaral et al. 2007; Sanchez–Donoso et al. 2012). The genetic infection constitutes a clear and present danger to the quail’s survival and migration (Sanchez–Donoso et al. 2014; Perennou 2009; Derégnaucourt 2000).

Morphology. The species is characterized by a plump body, short tail, short broad wings, and strong short legs (Cramp & Simmons 1980).

- Measures and Weights. The smallest member of its family in Israel and the Levant, its length is 16–18 cm, its wingspan 32–35 cm, and it weighs between 70 and 155 gr. (Cramp & Simmons 1980).

- Colors. The quail generally camouflages itself. The male differs in color from the female throughout the year, exhibiting sharper tones—a black throat, yellowish–brown body, streaked back and sides, creamy belly, a large and varied head pattern, and dark collar around his neck. Although the young resemble the female, it always has stripes under the cheek (Cramp & Simmons 1980; Del Hoyo et al. 1994).

Habitat. The quail is to be found from the northern borealis zone through to the temperate zone, steppe, and Mediterranean regions. It avoids snow and extreme desert areas (Cramp & Simmons 1980), generally preferring warm zones (Huntley et al. 2007). It frequents open areas, such as grain fields and vegetation–rich environments (also for nest shelter), and eschews forest fringes and fences (Johnsgard 1988; Sardà–Palomera et al. 2012). It is attracted to heavily fertilized crops, perhaps due to the size and density of the seeds (Tryjanowski et al. 2005; Blüthgen et al. 2012). It is unaffected by changes in cultivated areas (Cramp & Simmons 1980). A study using radio transmitters conducted on East German farmland indicates that quails prefer medium–sized vegetation in dense, weed–covered, sandy soil (Herrmann & Dassow 2006).

Life History

The quail lays 8–13 eggs in the ground. The chicks emerge altogether, open–eyed and self–feeding after 16-17 days of incubation (Ainsworth et all 2010). Although they leave the nest site after 11 days, they only reach full sexual maturity at less than one year (Glutz von Blotzehim et al. 1973). In their natural habitat, they live a maximum of 11 years (Del Hoyo et al. 1994). The quail’s long–distant migratory habits make it a vulnerable species—one of the chief factors affecting in the size of its population (Sanderson et al. 2009).

Characteristics that Appear in the Bible

General Distribution and Population. The quail has a wide Palearctic distribution (Johnsgard 1988; Del Hoyo et al. 1994). Its principal breeding distribution ranges from Eurasia and the Near–East through to North Africa, India, and China (Alderton 1992; Hoffmann 1988; Del Hoyo et al. 1994). Almost all its populations winter primarily in Africa and Southeast Asia, most commonly in the desert and semi–desert regions of the sub–Saharan belt, where they make themselves active amongst the dense vegetation (Cramp & Simmons 1980; Moreau 1966).

Distribution and Population in Israel. The quail is a regular passenger across most parts of the country, although uncommon (small numbers) in winter and summer (especially in the Beit Shean Valley and Judean Desert). It also rarely breeds in the north and central valleys (Shirihai 1996; Svensson et al. 1999). According to Tristram (1884), tens of thousands return in one night in March. Many also remain to breed in open plains, marshes, and corn fields in the Jordan basin and north of the country.

Flight. Its short, wide wingspan gives the quail a large wing load (Cramp & Simmons 1980). Its wings are significantly longer than other members of the same family, however, allowing it to fly fast and low in quick flaps over short distances to escape danger (Svensson et al. 1999).

Migration and Appearance in the Eastern Mediterranean. The peak of migration in the autumn is mid–September, the spring peak being April (Cramp & Simmons 1980; Moreau 1972). In Israel, the spring migration climaxes between 8 March and 8 April, mostly in the center and east of the country. The autumn peak is between 9 September and 22 September, occurring most commonly along the Mediterranean coastline (Shirihai 1996).

Migration customarily takes place at night, young chicks less than two months old being reported as passengers (Johnsgard 1988; Alderton 1992). This  species is the only one in its family to exhibit in a long–term migration pattern. The various Old World populations of the sub–species Coturnix c. coturnix follow three principal migration routes: 1) the Near East to east Africa (the Syria–Egypt route); 2) the Central Europe region to central Africa (the Italy–Tunis route); and 3) the West–Atlantic region to north and west Africa (the Iberia–Morocco route) (Handrinos & Akriotis 1997). These long distant migratory habits place the quail at risk, forming one of the primary contributing factors to the reduction in its population (Sanderson et al. 2009).

species is the only one in its family to exhibit in a long–term migration pattern. The various Old World populations of the sub–species Coturnix c. coturnix follow three principal migration routes: 1) the Near East to east Africa (the Syria–Egypt route); 2) the Central Europe region to central Africa (the Italy–Tunis route); and 3) the West–Atlantic region to north and west Africa (the Iberia–Morocco route) (Handrinos & Akriotis 1997). These long distant migratory habits place the quail at risk, forming one of the primary contributing factors to the reduction in its population (Sanderson et al. 2009).

In addition to Israel and the Levant, large numbers of quail also arrive from the northeastern populations, from Mongolia (route 1). Those that land on the shores of Gaza and Sinai come from central Europe and Turkey (route 2) (Baha el Din et al. 1989). These then migrate south to the Sahara, primarily across Senegal to Ethiopia and Kenya (Cramp & Simmons 1980; Del Hoyo et al. 1994). Some wandering in this species was observed from Tunisia to Morocco and vice versa (route [3]; Toschi 1956).

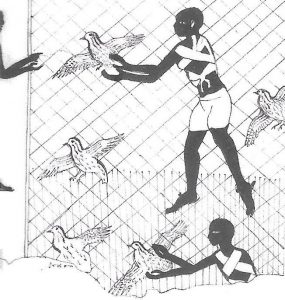

A Hunted Bird because Edible. Ancient Egyptian art—tombs at Sakkara, Thebes, and El–Arish, for example—depicts the quail as hunted with nets for food, being an edible bird (Moyal 2007). Today, it is still a gourmet meat, heavily hunted during the autumn migration, particularly in the Mediterranean (Gallego et al. 1997; Puigcerver et al. 1999; Sardà–Palomera et al. 2012). Its gastronomic value has led to its being extensively hunted in southern European (e.g., Catalonia) and other countries (Garrido 2012). It is also bred in large numbers in order to ensure the availability of sport–hunting from the end of the breeding season to the beginning of the next one (Rodríguez–Teijeiro et al. 2003).

A Hunted Bird because Edible. Ancient Egyptian art—tombs at Sakkara, Thebes, and El–Arish, for example—depicts the quail as hunted with nets for food, being an edible bird (Moyal 2007). Today, it is still a gourmet meat, heavily hunted during the autumn migration, particularly in the Mediterranean (Gallego et al. 1997; Puigcerver et al. 1999; Sardà–Palomera et al. 2012). Its gastronomic value has led to its being extensively hunted in southern European (e.g., Catalonia) and other countries (Garrido 2012). It is also bred in large numbers in order to ensure the availability of sport–hunting from the end of the breeding season to the beginning of the next one (Rodríguez–Teijeiro et al. 2003).

Coturnism. Poisoning by quail flesh has been documented since antiquity (Aristotle). Most cases, the symptoms are generalized weakness, progressing to severe muscle pain and lower limb paralysis accompanied by fever and voice loss—followed by death from cardiac or kidney failure.  Quail are toxic in Algeria and France during the northward spring migration. This pattern is reversed in Greece and the Soviet Union, where they are poisonous on the southern autumn flight. Current evidence suggests that seeds from the Stachys annua may serve as the mediating mechanism (Lewis et al. 1987).

Quail are toxic in Algeria and France during the northward spring migration. This pattern is reversed in Greece and the Soviet Union, where they are poisonous on the southern autumn flight. Current evidence suggests that seeds from the Stachys annua may serve as the mediating mechanism (Lewis et al. 1987).

Other Characteristics

Diet. Although an omnivore, the quail feeds primarily on plant–rich proteins—such as cereals and legumes—and insects and their larvae (Johnsgard 1988; Alderton 1992). It forages for food principally early in the morning and late in the afternoon (Dement’ev et al. 1966). Quail meat can be used as an alternative choice because it contains high high level protein (Kartikayudha et al., 2013).

It also feeds on flax and lupine (Herrmann & Dassow 2006), prior to embarking on its autumn migration also eating poisonous plant seeds such as Stachys sp. and Helleborus sp. of the Ranunculaceae family (Lewis et al. 1987).

Breeding and Nesting. Quail are customarily monogamous, the couple bond often being very strong (Johnsgard 1988). In rare cases, they also engage in bigamous and polygamous relations (Naumann 1833). During breeding season, the species is both solitary and territorial (Ali & Ripley 1969). The chicks reach sexual maturity at one- year old (Glutz von Blotzehim et al. 1973).

Most European quail populations breed for the first time in March–April, in North Africa and the Mediterranean basin. They then migrate to their principal breeding zones in central and northern Europe for a second breeding cycle in late May to July (Guyomarc’h et al. 1998). Quails hold up to two nesting cycles which take place in Europe ground in mid-May to August; but in Africa, they have up to three nesting cycles— from between the end of August to March (Johnsgard 1988). This species nestles primarily in grains and low dense vegetation, which hides them well (Moreau & Wayre 1968; Guyomarc’h & Guyomarc’h 1992).

According to a study based on well–controlled serenity, males are very nomadic, most not remaining longer than two weeks at a single site (Herrmann & Dassow 2006). Reaching the nesting sites before the females, they immediately commence courting rituals—loud territorial songs. Later, these become gentle and rhythmic, being rapidly repeated (Svensson et al. 1999).

When the females arrive, they locate the potential nesting site and begin responding to the males with soft attraction calls. The ritual continues with the males approaching in circular dances while squeezing their chest feathers, lowering their wings, stretching their necks, and uttering soft cries (Glutz von Blotzehim et al. 1973; Johnsgard 1988).

The nest—a shallow pit built on the grass and filled with available vegetation—is prepared by the female alone (Cramp & Simmons 1980; Johnsgard 1988). She lays 8–13 white eggs (Hoffmann 1988), which take 17–20 days to incubate (Alderton 1992). In Europe, the quail nests twice between May and August. In Africa, they nest up to three times between late August and March.

On some occasions, two females lay eggs in the same nest (Johnsgard 1988)—or, more rarely, in those of related species (Casas et al. 2006; Cramp & Simmons 1980; Yom-Tov 2001; Rodríguez–Teijeiro et al. 2003). While the eggs hatching asynchronously, the chicks are all the same age (Cramp & Simmons 1980).

Although the chicks may leave the nest as early as 11 days old (Alderton 1992; Hoffmann 1988; Johnsgard 1988), they usually do so after 19 days, becoming independent after between 30 and 50 days (Cramp & Simmons 1980).

Bibliography

Aharoni, I. 1924. Zoology. Tel Aviv: Hotza’at Kohelet (Hebrew).

Ainsworth, S.J., Stanley, R.L. Evan, D.J.R.. 2010. Development stage of the Japanese quail. Anat 216(1):3-15.

Alderton, D. 1992. The Atlas of Quails. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications.

Ali, S., and S.D. Ripley. 1969. Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 1. Bombay: Oxford University Press.

Amaral, A., A.R. Grosso, A.B. Silva, and L. Chikhi. 2007. “Detection of Hybridization and Species Identification in Domesticated and Wild Quails Using Genetic Markers.” Folia Zoologica 56(3): 285–300.

Baha el Din, M., J. Hobbs, and W.C. Mullie. 1989. “Quail Coturnix coturnix.” Pages 214–16 in The Birds of Egypt. Edited by S.M. Goodman and P.L. Meninger. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barilani, M., S. Derégnaucourt, S. Gallego, L. Galli, N. Mucci, R. Piombo, M. Puigcerver, S. Rimondi, and J. D. Rodríguez 2005. “Detecting Hybridization in Wild (Coturnix c. coturnix) and Domesticated (Coturnix c. japonica) Quail Populations.” Biological Conservation 126(4): 445–55.

Blüthgen, N., C.F. Dormann, D. Prati, V.H. Klaus, T. Kleinebecker, N. Hölzel, F. Alt, S. Boch, S. Gockel, A. Hemp, J. Müller, J. Nieschulze, S.C. Renner, I. Schöning, U. Schumacher, S.A. Socher, K. Wells, K. Birkhofer, F. Buscot, Y. Oelmann, C. Rothenwöhrer, C. Scherber, T. Tscharntke, C.N. Weiner, M. Fischer, E.K.V. Kalko, K.E. Linsenmair, E.D. Schulze, and W.W. Weisser. 2012. “A Quantitative Index of Land–use Intensity in Grasslands: Integrating Mowing, Grazing and Fertilization.” Basic Applied Ecology 13: 207–20.

Casas, F., D. Morrish, and J. Viñuela. 2006. “Parasitismo de nidada intraespefifico en la perdiz roja (Alectoris rufa).” Paper presented at the XI Congreso Nicional y VIII Iberoamericao de Etologica, Puerta de la Cruz, Tenerife, Spain.

Cramp, S., and K.E.L. Simmons. 1980. The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Del Hoyo, J., A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal. 1994. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Barcelona: Lynx.

Dement’ev, G.P., N.A. Gladkov, Y.A Isatov., N.N. Kartashev, S.V. Kirikov, A.V. Mikhee, and E.S. Ptushenko. 1966. Birds of the Soviet Union. Vol. 4. Translated from Russian by A. Birron and Z.S. Cole. Jerusalem: Israel Program for Scientific Translations.

Derégnaucourt, S. 2000. “Hybridization entre la caille des biés (Coturnix c. coturnix) et la caille japonaise (Coturnix c. japonica): Mise en evidence des risques de pollutions génetique des population naturelles par les cailles domestiques.” PhD thesis, Université Rennes I.

Gallego, S., M. Puigcerver, and J.D. Rodríguez–Teijeiro. 1997. “Quail Coturnix coturnix.” Pages 214–15 in The EBCC Atlas of European Breeding Birds: Their Distribution and Abundance. Edited by E.J.M. Hagemeijer and M.J. Blair. London: T. and A. D. Poyser

Geffen, E., and Y. Yom–Tov. 2001. “Factors Affecting the Rates of Intraspecific Nest Parasitism among Anseriformes and Galliformes.” Animal Behavior 62: 1027–38.

Garrido, J.L. 2012. La caza, Sector económico: Valoración por subsectores. Madrid: FEDENCA–EEC.

Glutz von Blotzehim, U.N., K.M. Bauer, and E. hand-Bezzel, 1973. Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas. Vol. 5. Frankfurt: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft.

Guyomarc’h, C. and J.C. Guyomarc’h, 1992. “Sexual Development and Free Running Period in Quail Kept in Constant Darkness.” Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 86: 103–110.

Guyomarc’h, C., O. Combreau, M. Pugicerver, P. Fontoura, N.J. Aebischer, and D.I.M. Wallace. 1998. Coturnix coturnix Quali. BWP Update 2: 27–46.

Handrinos, G., and T. Akriotis. 1997. The Birds of Greece. London: Christopher Helm.

Herrmann, M., and A. Dassow. 2006. “Quail Coturnix coturnix.” Pages 194–203 in Nature Conservation in Agricultural Ecosystems: Results of the SchorfheideChorin Research Project. Edited by M. Flade, H. Plachter, R. Schmidt, and A. Werner. Wiebelsheim: Quelle and Meyer.

Hoffmann, E. 1988. Coturnix Quail. Canning, Nova Scotia: Hoffmann.

Huntley, B., R.E. Green, Y.C. Collingham, and S.G. Willis. 2007. A Climatic Atlas of European Breeding Birds. Barcelona: Lynx.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1988. The Quails, Partridges, and Francolins of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kartikayudha W, Isroli, N.H. Suprapti, T.R. Saraswati. 2013. Muscle Fiber Diameter and Fat Tissue Score in Quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) Meat as Affected by Dietary turmeric (Curcuma longa) Powder and Swangi Fish (Priacanthus tayenus) Meal. Journal of the Indonesian Tropical Animal Agriculture 38 (4): 264-272.

Lewis, D.C., E. Metallinos–Katzaras, and L.E. Grivetti. 1987. “Coturnism: Human Poisoning by European Migratory Quail.” Journal of Cultural Geography 7(2): 51–65.

Mendelssohn, H., U. Marder, and Y. Yom–Tov. 1969. “On the Decline of the Migrant Quail (Coturnix c. coturnix) Population in Israel and Sinai.” Israel Journal of Zoology 18: 317–23.

Moreau, R.E. 1966. The Bird Fauna of Africa and its Islands. London: Academic Press.

Moreau, R.E. 1972. The Palaearctic–African Bird Migration Systems. London: Academic Press.

Moreau, R.E., and P. Wayre. 1968. “On the Palearctic Quail.” Ardea 56: 209–26.

Moyal, H. 2004. Lexicon of Vertebrates Names in Israel. Herzliya: Hotza’a Teva Hadevarim (Hebrew).

Moyal, H. 2007. “The Quail in Ancient Egyptian Culture.” Teva Hadevarim 138: 92–99 (Hebrew).

Naumann, J.F. 1833.. Naturgeschichte der Vögel Mitteleuropas. Vol 1. Gera–Untermhaus: Eugen Köhler.

Paz, U. 1986. Plants and Animals of the land of Israel, vol 6, Aves. Ministry of Defense and the SPNI.

Perennou, C. 2009. European Union Management Plan 2009–2011: Common Quail, Coturnix coturnix. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Puigcerver, M., S. Gallego, and J.D. Rodríguez–Teijero. 1989. “La caille des blés en Catalogne (Espagne): Quelques données sur sa biologie et son comportement.” Bulletin mensuel de L’Office national de la Chasse 138: 37–39.

Puigcerver, M., S. Gallego S., J.D. Rodríguez–Teijero, S. D’Amico, and E. Randi. 1999. “Hybridization and Introgression of Japanese Quail Mitochondrial DNA in Common Quail Populations: A Preliminary Study.” Hungarian Small Game Bulletin 5: 129–36.

Rodríguez–Teijeiro, J.D., M. Puigcerver, S. Gallego, P.J. Cordero, and D.T. Parkin. 2003. “Pair Bonding and Multiple Paternity in the Polygamous Common Quail Coturnix coturnix.” Ethology 109: 291–302.

Sanchez–Donoso, I., C. Vilà, M. Puigcerver, D. Butkauskas, J.R. Caballero De La Calle, P.A. Morales–Rodríguez, and J.D. Rodríguez–Teijeiro. 2012. “Are Farm–Reared Quails for Game Restocking Really Common Quails (Coturnix coturnix)?: A Genetic Approach.” PLoS ONE 7(6): e390312012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039031.

Sanchez–Donoso, I., J. Domingo Rodríguez-Teijeiro, I. Quintanilla, I. Jiménez-Blasco, F. Sardà-Palomera, J. Nadal, M. Puigcerver, and C. Vilà. 2014. “Influence of Game Restocking on the Migratory Behaviour of the Common Quail, Coturnix coturnix.” Evolutionary Ecology Research 16: 493–504.

Sanderson, F.J., K. Sachanowicz, and P.F. Donald. 2009. “Predicting the Effect of Agricultural Change on Farmland Bird Populations in Poland.” Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 129: 37–42.

Sardà–Palomera, F., M. Puigcerver, L. Brotons, and J.D. Rodríguez–Teijeiro. 2012. “Modelling Seasonal Changes in the Distribution of Common Quail Coturnix coturnix in Farmland Landscapes Using Remote Sensing.” Ibis 154: 703–13.

Shirihai, H. 1996. The Birds of Israel. London: Academic Press.

Svensson, S., M. Svensson, and M. Tjernberg. 1999. Swedish Bird Atlas. Vår Fagelvård Supplement 31. Stockholm: Sveriges Ornitologiska Förening.

Toschi, A. 1956. “Esperienze sul comportamento di quaglie (Coturnix c. coturnix L.) a migrazione interrotta.” Ricerche de Zoologia Applicata Alla Caccia 27: 1–275.

Tristram, H.B. 1884. The Flora and Fauna of Palestine. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

Tryjanowski, P., L. Jerzak, and J. Radkiewicz. 2005. “Effect of Water Level and Livestock on the Productivity and Numbers of Breeding White Storks.” Waterbirds 28: 378–82.

Yom-Tov, Y. 2001. “An Updated List and Some Comments on the Occurrence of Intraspecific Nest Parasitism in Birds.” Ibis a143: 133–43.

Contributor: Dr. Haim Moyal, Ornithologist, Zoologist, and archaeologist, Levinsky-Wingate College