Date palm, תָּמָר, Phoenix dactylifera

Back to FloraDate palm

תָּמָר, tāmār

Phoenix dactylifera

Modern Hebrew: תָּמָר, tāmār; דֶּקֶל, deqel

Biblical data

Introduction

The common noun תָּמָר (tāmār) occurs four times in the Hebrew Bible in the singular (Joel 1:12; Ps 92:13; Song 7:8, 9) and on four further occasions in the plural תְּמָרִים); təmārîm) (Exod 15:27 ≈ Num 33:9; Lev 23:40 ≈ Neh 8:15). While the singular of botanical terms frequently designates the living plant and the plural its usable product, in the present case both forms appear to denote the living plant (cf. most strikingly Neh 8:15).

This noun also serves as an element in four geographic names: תָּמָר (tāmār) (1 Kgs 9:18;[1] Ezek 47:19 ≈ 48:28); עִיר הַתְּמָרִים (ˁîr hattəmārîm “the city of təmārîm,” Deut 34:3; Judg 1:16; 3:13; 2 Chr 28:15)—explicitly identified with Jericho (Deut 34:3; 2 Chr 28:15); חַצְצֹן תָּמָר (ḥaṣəṣōn tāmār, Gen 14:17; 2 Chr 20:2)—explicitly identified with עֵין גֶּדִי (2 Chr 20:2); and בַּעַל תָּמָר (baˁal tāmār, Judg 20:33). The singular also serves as the personal name of three female characters: Judah’s daughter-in-law (Gen 38:6, 11 [x 2], 13, 24; Ruth 4:12; 1 Chr 2:4), Absalom’s sister (2 Sam 13:1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 [x 2], 19, 20, 22, 32; 1 Chr 3:9), and Absalom’s daughter (2 Sam 14:27).

The singular form תֹּמֶר (tōmer) occurs twice (Judg 4:5;[2] Jer 10:5[3]).[4]

The possibly derivative common noun תִּמֹרָה (timōrâ) occurs 19 times (1 Kgs 6:29, 32 [x 2], 35; 7:36; Ezek 40:16, 22, 26, 31, 34, 37; 41:18 [x 2], 19 [x 2], 20, 25, 26; 2 Chr 3:5).

Distribution within the Bible

The tree is mentioned eight times in the Bible in the form תָּמָר / תְּמָרִים:

- Thrice in narrative (Exod 15:27; Num 33:9; Neh 8:15)

- Twice in love poetry (Song 7:8, 9)

- Once in legal material (Lev 23:40)

- Once in prophecy (Joel 1:12)

- Once in psalmody (Ps 92:13)

Toponyms that include the form as an element occur ten times:

- Eight in narrative (Gen 14:7; Deut 34:3; Judg 1:16; 3:13; 20:33; 1 Kgs 9:18; 2 Chr 20:2; 28:15)

- Two in prophecy (Ezek 47:19; 48:28)

The form תֹּמֶר occurs twice in the Bible:

- Once in narrative (Judg 4:5)

- Once in prophecy (Jer 10:5)

The word תִּמֹרָה occurs 19 times, all within a temple context:

- Six times in narrative descriptions of Solomon’s temple (1 Kgs 6:29, 32 [x 2], 35; 7:36; 2 Chr 3:5)

- 13 times in Ezekiel’s vision of the rebuilt temple (Ezek 40:16, 22, 26, 31, 34, 37; 41:18 [x 2], 19 [x 2], 20, 25, 26)

Parts, Elements, Features that Are Specified in the Bible

Leaves. כַּפֹּת (Lev 23:40)—literally “palms” (BDB, s.v.כַּף 4d). These are presumably the leaves (see Neh 8:15), whose collective resemblance to the palm of a hand gave the name “palm” to this kind of tree in Latin and English.

Withering, due to locusts (Joel 1:12).

Blossoming or flourishing (Ps 92:13).

Height (Song 7:8), potential to be climbed (Song 7:9).

Fruit clusters (Song 7:8).

סַנְסִנִּים—graspable (Song 7:9), understood as the crown (Septuagint), leaves (Peshitta; Symmachus; Targum to Songicles), spathes (Aquila), fruits (Vulgate), spadices (Löw 1881) / fruit stalks (BDB) / panicles (HALOT), fruit clusters (Viezel 2014), or leaf bases (Eichler 2020).

Function in Context

The realistic references relate to its growth in the wilderness between Egypt and the Land of Israel (Exod 15:27; Num 33:9), the use of the כַּפֹּת for the Festival of Booths (Lev 23:40), the use of the leaves in the Land of Israel to construct the booths (Neh 8:15), and its withering following a locust attack (Joel 1:12).

תֹּמֶר: its growth in the Ephraimite hill-country in the Land of Israel (Judg 4:5).

תִּמֹרָה: as decoration in sacred places (1 Kgs 6:29, 32 [x 2], 35; 7:36; Ezek 40:16, 22, 26, 31, 34, 37; 41:18 [x 2], 19 [x 2], 20, 25, 26; 2 Chr 3:5).

Simile: the flourishing or blossoming of a righteous person (Ps 92:13), a woman’s height and perhaps erect posture, her breasts resembling its fruit clusters (Song 7:8).

תֹּמֶר: idols (Jer 10:5).[5]

Metaphor: climbing it and grasping its סַנְסִנִּים symbolize an erotic act of a man with a woman (Song 7:9).

Pairs and Constructions

It is collocated with springs of water, presumably to indicate habitability (Exod 15:27; Num 33:9).

It appears in lists of plant products used for celebrating the Festival of Booths:פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר כַּפֹּת תְּמָרִים וַעֲנַף עֵץ־עָבֹת וְעַרְבֵי־נָחַל (“the product of hadar trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook,” Lev 23:40) and in the booth construction itself:עֲלֵי־זַיִת וַעֲלֵי־עֵץ שֶׁמֶן וַעֲלֵי הֲדַס וַעֲלֵי תְמָרִים וַעֲלֵי עֵץ עָבֹת (“leafy branches of olive trees, pine trees, myrtles, palms and [other] leafy trees,” Neh 8:15).

It forms part of a list of fruit trees destroyed by locusts: הַגֶּפֶן … וְהַתְּאֵנָה … רִמּוֹן גַּם־תָּמָר וְתַפּוּחַ כָּל־עֲצֵי הַשָּׂדֶה (“The vine has dried up, the fig tree withers, pomegranate, palm, and apple—all the trees of the field are sear,” Joel 1:12).

It is paired with אֶרֶז (Ps 92:13).

It is collocated with גֶּפֶן and תַּפּוּחִים (Song 7:9).

End Notes

[1] The toponym appears in the parallel passage in Chronicles (2 Chr 8:4) as תַּדְמֹר. The ancient translations of Chronicles agree with this reading (Septuagint: Θεδμορ; Peshitta: tdmwr; Vulgate: Palmyram; Targum of Chronicles: תדמור), as do many textual witnesses to the book of Kings (qere in many MT manuscripts: תַּדְמֹר; Septuagint [1 Kgs 2:46d]: Θερμαι; Lucianic manuscripts: θαδαμορ/θοδμορ; Targum Jonathan: תַדמוֹר; Peshitta: tdmwr; Vulgate: Palmyram [Tadmor]). תָּמָר should nonetheless be preferred.

[2] The full verse segment is: וְהִיא יוֹשֶׁ֨בֶת תַּֽחַת־תֹּ֜מֶר דְּבוֹרָ֗ה בֵּ֧ין הָרָמָ֛ה וּבֵ֥ין בֵּֽית־אֵ֖ל בְּהַ֣ר אֶפְרָ֑יִם, apparently: “She [Deborah] used to sit under the tomer of Deborah between the Ramah and Bethel in the Ephraimite hill-country”—although the masoretic Songillation signs separate tomer and Deborah. While “Tomer of Deborah” may be understood as a toponym, this reading makes the word תַּחַת “under” difficult.

[3] The Septuagint appears to reflect the reading כתם rather then כתמר here: see BHK; BHS; Tov et al. 1997.

[4] While תָּמָר and תֹּמֶר may represent the same lexeme, they appear as separate entries in most dictionaries (Gesenius, Thesaurus; BDB; HALOT; DCH). The abnormal vocalization of tmr as tomer in Judg 4:5 and Jer 10:5 may have been prompted by the fact that these are the only two places in which it appears to be in the construct. Biblical Hebrew attests to a variety of abnormal vocalizations within the inflections of qatal nouns: see GKC, §93dd; Joüon, §96Bb. For more on the form תֹּמֶר, see Eichler 2017, passim.

[5] For the possible meanings of this simile, see Eichler 2017, passim.

Bibliography

Eichler, Raanan. 2017. “Jeremiah and the Assyrian Sacred Tree.” VT 67(3): 403–413.

Eichler, Raanan. 2020. “The Tree-Hugger Who Went on a Date: The Meaning of sansan.” VT 70(4): 581–591.

Löw, Immanuel. 1881. Aramäische Pflanzennamen. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

Tov, Emanuel et al., eds. 1997. Jeremiah. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Bible Project (Hebrew).

Viezel, Eran. 2014. “סַנסְִנּיָו (sansinnāyw; Song of Songs 7:9) and the Palpal Noun Pattern.” JBL 133(4): 751–756.

Contributor: Dr. Raanan Eichler, Department of Bible Studies, Bar Ilan University

History of Identification

Identification History Table

Life & Natural Sciences

English: Date palm

Hebrew: תָּמָר (tāmār)

Scientific Name: Phoenix dactylifera

ID

Kingdom: Plantae

Division: Angiospermae

Class: Monocotyledoneae

Order: Arecales

Family: Arecaceae

Genus: Phoenix

Species: Phoenix dactylifera

Commonly known as the date palm, the Phoenix dactylifera (Latin for ‘date-bearing’ [Liddell & Scott 1861]) is a flowering plant species of the Arecaceae family, native to tropical and subtropical areas of Asia and Africa. A flowering monocotyledon (Krueger 2021), its seeds contain an embryo with only one embryonic leaf, also called a cotyledon—other flowering plants being dicotyledons, since they have two cotyledons. Most monocotyledons are herbaceous, possessing little or no woody tissue and customarily lasting over one growing season. Only a small number being trees, the P. dactylifera is thus unusual. Monocotyledon trees exhibit unique anatomical characteristics: not creating growth rings, it is difficult to estimate their age (Zaid & de Wet 2002), for example. Slow-growing, they can live over 100 years and reach 30m in height (Hodel, Johnson, & Nixon 2007).

Life History

The date palm is a slow-growing tree that can reach over 100 years of age (Hodel et al. 2007). In Israel, its fruit begin forming around June, customarily ripening between August and October. The flowers bloom between the end of March and the beginning of June (www.flora.org.il; Feldman 1956, 43–48).

Characteristics that Appear in the Bible

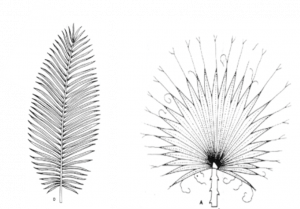

Palm-shaped leaves. Members of the Arecaceae family have large evergreenleaves that are either palmate (“fan-leaved”) or pinnate (“feather-leaved”), arranged spirally at the top of the stem. The only genus with pinnate leaves, the Phoenixgenus is unique among its subfamily (Riffle & Craft 2003).

Withering due to Locusts. P. dactylifera leaves are particularly vulnerable to two locust species—the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) and the Egyptian locust (Anacridium aegyptium). Both these species inhabit habitats similar to those of the Phoenix dactylifera (El-Shafie 2012).

Tall, Erect Trees that Can Be Climbed. The Phoenix dactylifera has a non-branching trunk that can reach 20m in height (Loutfi & El Hadrami 2005; Zaid & de Wet 2002). Pollination is essential for the formation of fruits—an important human commodity. Although this process occurs naturally via the wind, techniques were invented early on to make it more efficient and economical for growers. Enabling farmers to scale the trees in order to collect the pollen from the male trees and transfer it to the female trees, these remain prevalent today (Abu-Zahra & Shatnawi 2019).

Blossoming and Flourishing Periods. An evergreen, the date palm blooms in the spring, and the fruit are being harvested from the end of the summer until mid-fall (for more specific information see life history section; (flora.org.il).

Grows in the Wild between Egypt and Israel, in the Ephraimite hill-country, and Close to Springs. The first signs of date-palm domestication in the Levant area date to ca. 6,500 BCE (Zohary et al. 2012)—approximately 5,000 years prior to the assumed “biblical period.” Those referred to in the biblical text were thus presumably domesticated rather than wild. Growing naturally in arid areas close to springs and/or easily accessible groundwater and requiring high temperatures (www.wildflowers.co.il), the date palm is found principally in Israel in oases—the Arava, Dead Sea Valley, and Lower Jordan Valley. Although less common on high places, it is also occasionally found in the Samarian and Judean mountains and Negev hills (www.flora.org.il; www.wildflowers.co.il). According to Judges, Deborah used to sit under the “tomer of Deborah” between Ramah and Bethel in the Ephraimite hill country (Judg 4:5). The Ephraimites settling in some parts of the Samarian mountains, date palms may have been native to this area (or transplanted in an early period), despite this not being their optimal habitat. Not many date palms were growing in the mountainous area, perhaps because there they hardly produce fruits, if at all. Hence, mountainous P. dactylifera were mostly used for their shade, wood and other tree parts (Halperin & Arnon, 1976).

Multiple Flowers and Clustered Fruits. The date palm’s male and female flowers grow in clusters (inflorescences). Known as spadices or spikes, these consists of a central stem (rachis) and several strands or spikelets (usually 50–150 lateral branches) (Zaid & de Wet 2002). Each of the latter carry between 8,000 and 10,000 female flowers and even more male flowers (Chandler 1958). The fruit develops from a single flower, thus being organized in clusters like the flowers, the species name dactylifera—signifying “finger-bearing”— referring to the shape of the fruit (Friedman et al. 2010).

Other Characteristics

Seed dispersal. Containing high carbohydrate levels, date palm fruits form a major part of the diet of resident and migratory bird species and fruit bats as well as a major agricultural crop in the (semi-)arid zone of North Africa and the Middle East. Studies evince dispersal distances ranging from dozens of meters to ca. 50km, carried by diverse bird species and terrestrial animals (primarily canids), bears, and flightless birds (e.g. the Emu [Dromaius novaehollandiae]; Spennemann 2018).

Interactions with Other Organisms. Rhynchophorus ferrugineus or the red palm weevil was first identified as harmful to the Indian coconut palm in 1906 (Lefroy 1906), subsequently also being implicated in date-palm damage in 1917 (Brand 1917). Following its discovery in the Gulf Region in the mid-1980s, the weevil spread rapidly to several date-producing countries via infested planting material, primarily transported for ornamental gardening (Faleiro et al. 2012). Now reported across Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas, the red palm weevil has thus become a worldwide phenomenon (Giblin-Davis et al. 2013). In recent years, R. ferrugineus has been responsible for wreaking the most insect devastation on palm plantations across the globe (Bertone, Michalak, & Roda 2010). The recommended method for dealing with this is integrative, combining strict quarantine measures, insect traps, careful pesticide treatment, additional natural enemies (biological control), etc. (Al-Dosary et al. 2016).

Morphological Characteristics

Trunk. The date palm trunk is called a stem or stipe. Shaped as a column, it exhibits no side branching. The girth of the trunk not increasing once the canopy of fronds has fully developed, it creates no growth rings. Either single stemmed or forming a clump with several stems from a single root system, it can reach 20 meters in height (Zaid & de Wet 2002).

Leaves. Date palm leaves are between three and six meters long, remaining functional for ca. 3–7 years. Their wide base narrows towards the top, both sides bearing between 10 and 60 spines. Unlike other fruit trees, the P. dactylifera does not shed its old leaves nor do they drop on their own, they are removed only under cultivation. An adult date palm has approximately 100–125 green leaves with an annual formation of 10–26 new leaves. Under good cultural conditions, one leaf can support 1‒1.5kg of dates (Zaid & de Wet 2002).

Flowers. A dioecious species, the date palm produces both male and female flowers in clusters on separate palms. In the early stages of growth, the inflorescence or flower cluster is enclosed in a hard covering known as a spathe. This protects the delicate flowers both mechanically and from harsh environmental conditions (Zaid & de Wet 2002). When the flowers have matured, the spatha splits open, exposing the inflorescence to pollination. The female inflorescence carries ca. 8,000‒10,000 tiny creamy-colored flowers, the male inflorescence an even higher number (Chandler 1958, 205–28; Zaid & de Wet 2002).

Male inflorescence of Phoenix dactylifera. Image was taken from www.flora.org.il. Credit: Dr. Ori Fragman-Sapir.

Fruit. The oblong-shaped fruit—known as a drupe—consists of an external shell, a fleshy part, and a single hardened seed (Zaid & de Wet, 2002).

Seeds. Seeds weigh between under 0.5 g–4g, vary in length between 12 and 36mm, and are between six and thirteen millimeters in breadth, being oblong in shape (Zaid & de Wet, 2002).

Roots. As a monocotyledon, the date palm has no tap root (a substantial root growing vertically downward). Its root system is thus formed by thin, branching roots that grow in clusters from the base of the stem. Its roots can thus extend as far as 25m from the palm and deeper than six meters (Munier 1973). This gives the tree access to ground water, allowing it to endure drought conditions for relatively long periods (Zaid & de Wet 2002).

Distribution and Habitat

Current distribution map of Phoenix dactylifera. Taken from www.gbif.org. In this map each point represents the number of species occurrence records. Darker colored points indicate more occurrences.

Grown in the arid regions of the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, and the Middle East (Chao & Krueger 2007), the date palm is a very ancient fruit crop. It has been domesticated for several millennia in its centers of origin, diversity and domestication in the Middle East and North Africa, thence spreading to other sandy, hot and (semi-)arid regions and oases that possess sufficient moisture in the form of groundwater or irrigation. Requiring large volumes of water for growth and fruit production, it tolerates saline conditions but is not truly adapted to extreme saline habitats (Krueger 2021).

Bibliography

Abdelhamid, M. M. 2020. “The Significance of the Date Palm as a Decorative Motif in the Synagogues of Cairo, Egypt.” International Journal of History and Cultural Studies 6.1: 1‒13: https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijhcs/v6-i2/1.pdf.

Abu-Zahra, T. R. and M. A. Shatnawi. 2019. “New Pollination Technique in Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Cv. ‘Barhee’ and ‘Medjol’ under Jordan Valley Conditions.” American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences 19: 37–42.

Al-Dosary, N. M. M., S. AlDobai and J. R. Faleiro. 2016. “Review on the Management of Red Palm Weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier in Date Palm Phoenix dactylifera L.” Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture 28: 34–44.

Bertone, C., P. S. Michalak and A. Roda. 2010. “New Pest Response Guidelines, Red Palm Weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus).” United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Cooperating State Departments of Agriculture: https://www.ippc.int/static/media/uploads/resources/new_pest_response_guidelines_red_palm_weevil.pdf.

Brand, E. 1917. “Coconut Red Weevil: Some Facts and Fallacies.” Tropical Agriculturist and Magazine of the Ceylon Agricultural Society 49: 22–24.

Chandler, W. H. 1958. Evergreen Orchards. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Fibiger.

Chao, C. T. and R. R. Krueger. 2007. “The Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.): Overview of Biology, Uses, and Cultivation.” Horticultural Science 42: 1077–82.

El-Shafie, H. A. F. 2012. “List of Arthropod Pests and their Natural Enemies Identified Worldwide on Date Palm, Phoenix dactylifera L.” Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America 3: 516–24.

Faleiro, J. R. A. et al. 2012. “Threat of Red Palm Weevil, Rhynchophorus Ferrugineus (Olivier) to Date Palm Plantations in North Africa.” Arab Journal of Plant Protection 30: 274–80.

Feldman, U. 1956. Plants of the Bible. Tel Aviv: Dvir (Hebrew).

Feliks, Y. 1968. Plant World of the Bible. Ramat-Gan: Masada (Hebrew).

Friedman, M. H. et al. 2010. Phoenix dactylifera, Date Palm (FOR 252). UF/IFAS Extension: University of Florida. FOR 252/FR314: Phoenix dactylifera, Date Palm (ufl.edu)

Giblin-Davis, R. M., J. R. Faleiro, J. A. Jacas, J. E. Peña and P. S. P. V. Vidyasagar. 2013. “Biology and Management of the Red Palm Weevil, Rhynchophorus Ferrugineus.” Pages 1‒34 in Potential Invasive Pests of Agricultural Crop Species, ed. J. E. Peña. Wallingford: CABI.

Hodel, D. R., D. V. Johnson and R. W. Nixon. 2007. “Imported and American Varieties of Dates (Phoenix Dactylifera) in the United States.” Oakland: University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. https://books.google.co.il/books?id=R0XjojWqfqcC&pg=PA13&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Stoller, S. 1976.“The Date.” Pages 211-218 in vol. 3 of The Agricultural Encyclopedia. Edited by Haim Halperin and Itzhak Arnon. 6 vols. Tel Aviv: The Agricultural Encyclopedia (Hebrew).

Johnson, D. V. 2011. Tropical Palms: 2010 revision (10/Rev. 1). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Krueger, R. R. 2021. “Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.): Biology and Utilization.” Pages 3–28 in vol. 1 of The Date Palm Genome. New York: Springer.

Lefroy, H. M. 1906. The More Important Insects Injurious to Indian Agriculture. Calcutta: Government Press.

Liddell, H. G. and Scott, R. 1861. A Greek–English Lexicon. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/efts/PERSEUS/Reference/minilsj.html

Loutfi, K. and I. El Hadrami. 2005. “Phoenix dactylifera, Date Palm.” Pages 144-156 in Biotechnology of Fruit and Nut Crops. Edited by Richard E. Litz. Biotechnology in Agriculture No. 29. Cambridge: CABI.

Munier, P. 1973. Le palmier-dattier: Techniques agricoles et productions tropicales. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose.

Popenoe, P. 1924. “The Date-Palm in Antiquity.” The Scientific Monthly 19(3): 313–25.

Riffle, R. L. and P. Craft. 2003. An Encyclopedia of Cultivated Palms. Portland: Timber.

Spennemann, D. H. R. 2018. “Review of the Vertebrate-mediated Dispersal of the Date Palm, Phoenix dactylifera.” Zoology in the Middle East 64(4): 283–96.

Zaid, A. and P. F. de Wet. 2002. “Botanical and Systematic Description of the Date Palm.” Pages 1‒11 in Date Palm Cultivation. Edited by A. Zaid and E. J. Arias-Jiménez. FAO Plant Production and Protection Papers 156, Rev. 1. Rome: FAO.

Zohary, D., M. Hopf and E. Weiss. 2012. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin. 4th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Contributor: Dr. Shira Penner Rosenvasser, Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel Aviv University